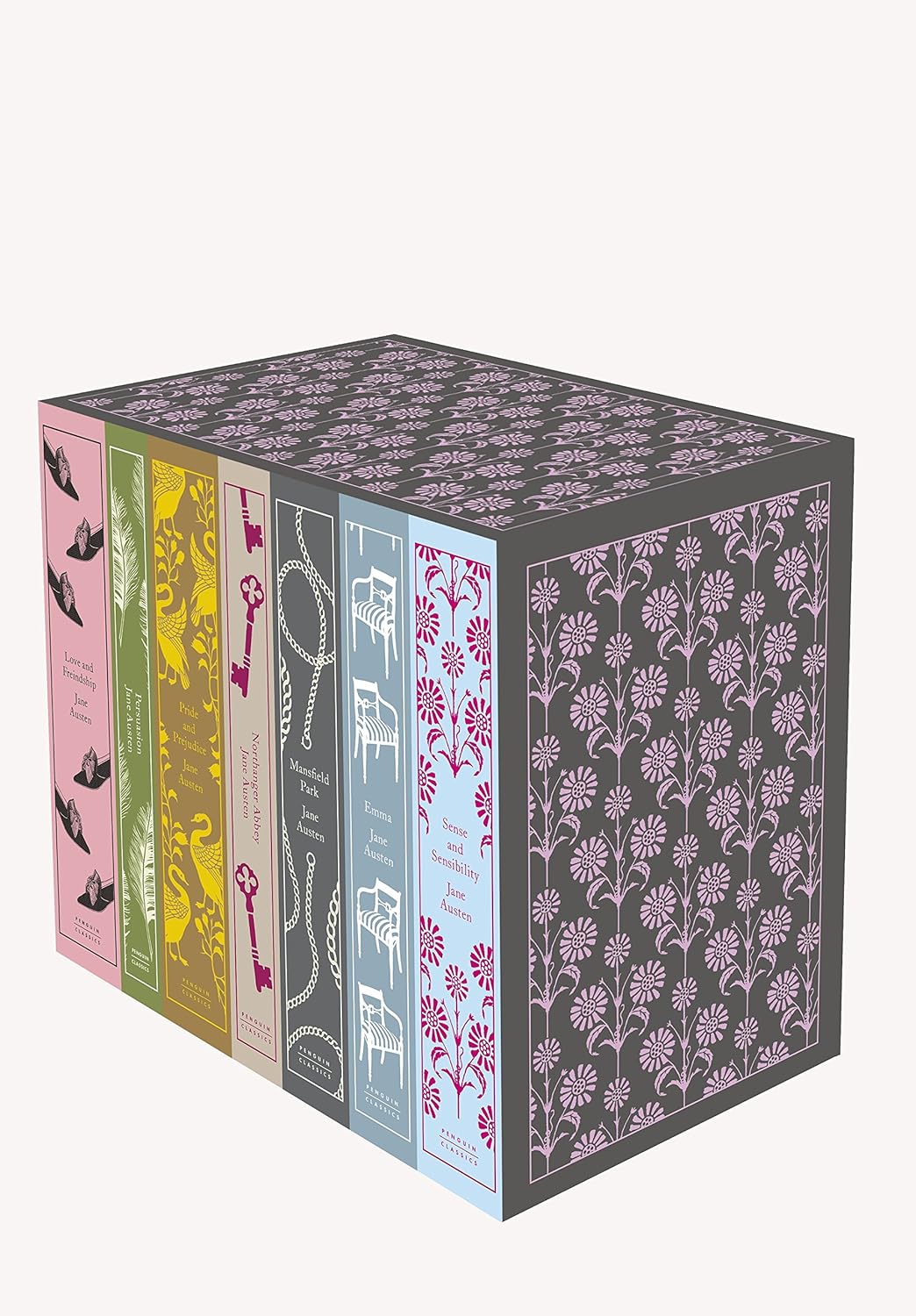

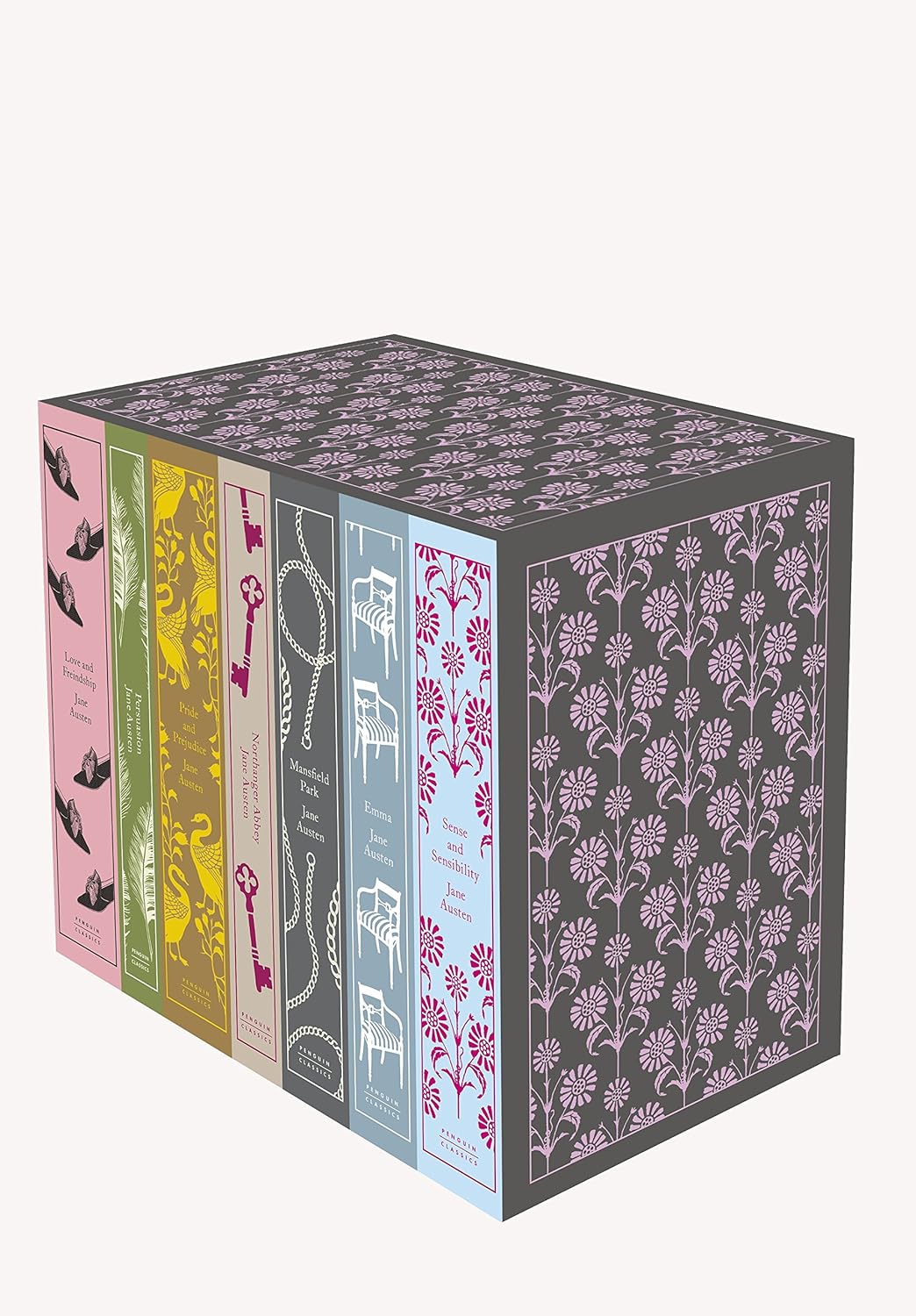

Jane Austen: The Complete Works: Classics Hardcover Boxed Set (Penguin Clothbound Classics)

FREE Shipping

Jane Austen: The Complete Works: Classics Hardcover Boxed Set (Penguin Clothbound Classics)

- Brand: Unbranded

Description

Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. New York: Harcourt Brace. p. 2. ISBN 0-15-195747-9. John Murray also published the work of Walter Scott and Lord Byron. In a letter to Cassandra dated 17/18 October 1816, Austen comments that "Mr. Murray's Letter is come; he is a Rogue of course, but a civil one." [116] Austen-Leigh, James Edward. A Memoir of Jane Austen. 1926. Ed. R.W. Chapman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967. hubbard, susan. "Bath". seekingjaneausten.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019 . Retrieved 27 May 2017.

Irene Collins estimates that when George Austen took up his duties as rector in 1764, Steventon comprised no more than about thirty families. [12] Waldron, Mary. "Critical Response, early". Jane Austen in Context. Ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-82644-6. 83–91 Austen-Leigh, William and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh. Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters, A Family Record. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1913. Le Faye, Deirdre, ed. Jane Austen's Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-283297-2. George Austen and Cassandra Leigh were engaged, probably around 1763, when they exchanged miniatures. [20] He received the living of the Steventon parish from Thomas Knight, the wealthy husband of his second cousin. [21] They married on 26 April 1764 at St Swithin's Church in Bath, by license, in a simple ceremony, two months after Cassandra's father died. [22] Their income was modest, with George's small per annum living; Cassandra brought to the marriage the expectation of a small inheritance at the time of her mother's death. [23]

Retailers:

From at least the time she was aged eleven, Austen wrote poems and stories to amuse herself and her family. [50] She exaggerated mundane details of daily life and parodied common plot devices in "stories [] full of anarchic fantasies of female power, licence, illicit behaviour, and general high spirits", according to Janet Todd. [51] Containing work written between 1787 and 1793, Austen compiled fair copies of twenty-nine early works into three bound notebooks, now referred to as the Juvenilia. [52] She called the three notebooks "Volume the First", "Volume the Second" and "Volume the Third", and they preserve 90,000 words she wrote during those years. [53] The Juvenilia are often, according to scholar Richard Jenkyns, "boisterous" and "anarchic"; he compares them to the work of 18th-century novelist Laurence Sterne. [54] Portrait of Henry IV. Declaredly written by "a partial, prejudiced, & ignorant Historian", The History of England was illustrated by Austen's sister, Cassandra (c.1790). Rajan, Rajeswari. "Critical Responses, Recent". Jane Austen in Context. Ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-82644-6. 101–10.

Austen letter to James Stannier Clarke, 15 November 1815; Clarke letter to Austen, 16 November 1815; Austen letter to John Murray, 23 November 1815, in Le Faye (1995), 296–298. Kelly, Gary. "Education and accomplishments". Jane Austen in Context. Ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-82644-6. 252–259 Alonso Duralde, Alonso, "'Love & Friendship' Sundance Review: Whit Stillman Does Jane Austen—But Hasn't He Always?", The Wrap, 25 January 2016. In 1802 it seems likely that Jane agreed to marry Harris Bigg-Wither, the 21-year-old heir of a Hampshire family, but the next morning changed her mind. There are also a number of mutually contradictory stories connecting her with someone with whom she fell in love but who died very soon after. Since Austen’s novels are so deeply concerned with love and marriage, there is some point in attempting to establish the facts of these relationships. Unfortunately, the evidence is unsatisfactory and incomplete. Cassandra was a jealous guardian of her sister’s private life, and after Jane’s death she censored the surviving letters, destroying many and cutting up others. But Jane Austen’s own novels provide indisputable evidence that their author understood the experience of love and of love disappointed.

Her education came from reading, guided by her father and brothers James and Henry. [44] Irene Collins said that Austen "used some of the same school books as the boys". [45] Austen apparently had unfettered access both to her father's library and that of a family friend, Warren Hastings. Together these collections amounted to a large and varied library. Her father was also tolerant of Austen's sometimes risqué experiments in writing, and provided both sisters with expensive paper and other materials for their writing and drawing. [46] It is more serious than it looks, as is usual with a good deal of her work, where the seemingly most superficial and romantic turns out to be most serious and worthy of note.

Later, it's the young Sir Edward Denham, handsome, and flattering in his attentions to the visitor Miss Charlotte Haywood, who is subject of the author's scrutiny. Philadelphia had returned from India in 1765 and taken up residence in London; when her husband returned to India to replenish their income, she stayed in England. He died in India in 1775, with Philadelphia unaware until the news reached her a year later, fortuitously as George and Cassandra were visiting. See Le Faye, 29–36Jane Austen is now on Britain's 10 pound note". ABC News. 14 September 2017 . Retrieved 4 December 2019. Trott, Nicola. "Critical Responess, 1830–1970", Jane Austen in Context. Ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-82644-6. 92–100 Watt, Ian, ed. Jane Austen: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1963.

Le Faye (2014), xxv–xxvi; Sutherland (2005), 16–21; Fergus (2014), 12–13, 16–17, n.29, 31, n.33; Fergus (2005), 10; Tomalin (1997), 256. Copeland, Edward and Juliet McMaster, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-521-74650-2. Austen lived her entire life as part of a close-knit family located on the lower fringes of the English landed gentry. She was educated primarily by her father and older brothers as well as through her own reading. The steadfast support of her family was critical to her development as a professional writer. Her artistic apprenticeship lasted from her teenage years until she was about 35 years old. During this period, she experimented with various literary forms, including the epistolary novel which she tried then abandoned, and wrote and extensively revised three major novels and began a fourth. From 1811 until 1816, with the release of Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma (1815), she achieved success as a published writer. She wrote two additional novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, both published posthumously in 1818, and began a third, which was eventually titled Sanditon, but died before completing it.

Read now or download (free!)

Austen's novels have resulted in sequels, prequels and adaptations of almost every type, from soft-core pornography to fantasy. From the 19th century, her family members published conclusions to her incomplete novels, and by 2000 there were over 100 printed adaptations. [180] The first dramatic adaptation of Austen was published in 1895, Rosina Filippi's Duologues and Scenes from the Novels of Jane Austen: Arranged and Adapted for Drawing-Room Performance, and Filippi was also responsible for the first professional stage adaptation, The Bennets (1901). [181] The first film adaptation was the 1940 MGM production of Pride and Prejudice starring Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson. [182] BBC television dramatisations since the 1970s have attempted to adhere meticulously to Austen's plots, characterisations and settings. [183] The British critic Robert Irvine noted that in American film adaptations of Austen's novels, starting with the 1940 version of Pride and Prejudice, class is subtly downplayed, and the society of Regency England depicted by Austen that is grounded in a hierarchy based upon the ownership of land and the antiquity of the family name is one that Americans cannot embrace in its entirety. [184] Le Faye, "Memoirs and Biographies". Jane Austen in Context. Ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-82644-6. 51–58

- Fruugo ID: 258392218-563234582

- EAN: 764486781913

-

Sold by: Fruugo